A notebook for fiction writers and aspiring novelists. One editor’s perspective.

• Next post • Previous post • Index

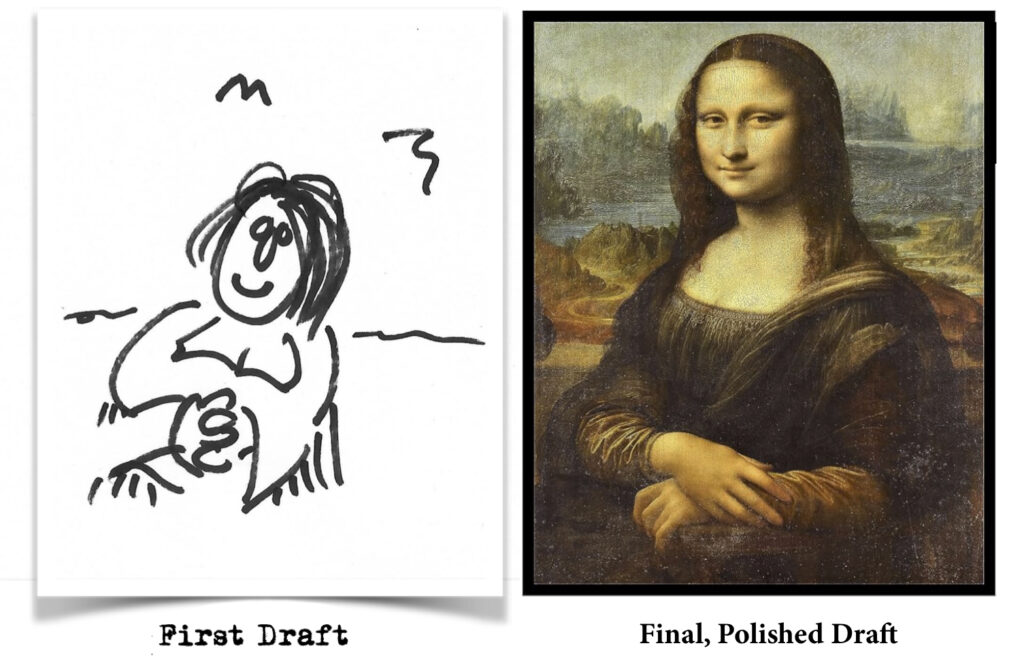

Don’t expect perfection in a first draft.

Don’t even expect coherence.

One’s first draft isn’t so much a solid entity as it is an amorphous, adaptive, multi-functional and cluttered embryonic mass that will one day give birth to a polished manuscript, ready for publication. This gestation process is part rough outline, part sketchpad, part journal, part cheat sheet, part receptacle and part dream-catcher for ideas both clever and foolish. (The foolish ones will be gradually, eventually replaced by bouts of brilliance, of course.)

Every writer will experience a unique and different approach to writing a first draft. (Spoiler: There ain’t no single way!) For some writers—not many, but a few—each page will emerge pristine and complete as is. Those writers are basically drafting, editing, re-editing and polishing each page in their heads before continuing to the next page. For the rest of us, however, our first draft is (or will be) a hot mess, filled with gaping plot holes and various discrepancies, half-baked thoughts and overtly flowery prose—all waiting for an eventual fix in subsequent drafts.

Writing (and finishing) a novel involves an intricate, two-step process: Part 1. The Idea. And, Part 2. The Implementation. The Idea (your original concept) is largely a Right Brain (creative thinking) process. The Implementation (writing it down) is mostly a Left Brain (critical thinking, problem solving) process. For most writers, creativity isn’t difficult. We’re all daydreamers at heart. Some of us are natural-born storytellers. Both the difficulty and the success of our efforts depend upon which of those ideas we choose and refine into relevant prose. Sometimes, the chasm between The Idea and The Implementation may seem impossible. (But it’s not!)

Part 1. The Idea: Perceiving a potential novel—those weeks or months or years spent contemplating a story—that’s pretty much quantum thinking. Fragmented concepts spin around our heads like graffiti at Marti Gras, thoughts about this-or-that coming and going in no particular order. But then we must gather the resulting chaos…

Part 2. The Implementation: Once a writer begins to put thoughts on paper, word after word after word, that’s linear thinking. Basically we’re taking a bloated, unwieldy (and sometimes incomplete) concept and filtering it through a very small cerebral nozzle—one painstaking sentence at a time.

A first draft is that fusion of quantum thinking crashing into linear thinking. Some thoughts will transcribe smoothly to the page, but others emerge kicking and screaming, not at all sure if or where they belong. But a first draft allows all those free-flowing thoughts a place to safely crash-land—many only temporarily—and then recover. Think of an oil painter who roughly sketches an idea on a canvas with a pencil before beginning to apply paint. A writer’s first draft is very much like that sketch. We’re not really sure what our final results will look like, but at least we have an idea. It’s a start.

The key to success, for most of us, is being aware of a first draft’s purpose. Don’t expect immediate satisfaction in a first draft. Because we’re not looking for any sort of perfection or brilliant prose (although we may see bits and pieces of future brilliance begin to take shape.) But a first draft is simply a tool meant FYEO, and one that often explores various options, opportunities and changes to our story before (or as) we find the best way forward. (Also see Perfection.)

Once you’ve cobbled your first draft together, reasonably sure of your story’s outcome, you may find it easier to begin adding depth and complexity to both your characters and your realm/location building—adding ‘color commentary’ to your plot structure. You may find room for intriguing side-stories and/or new supporting characters. There really is no solid definition for what a ‘second draft’ might entail. Some of us will revisit pages chronologically, others (myself included) will make random passes at random sections of the book—sometimes rewriting scenes or sequences a dozen times or more, ’til I ‘get it right.’ Again, there’s no single way to proceed at this point—there’s only the methodology that works best for you.

A Comprehensive, Illustrative Guide to the

Intentionality and Complexity of a First Draft

Essential Q & A

Q. What’s the difference between an outline and a first draft?

A. Typically (not always, but often) an outline can be created as a prelude to a first draft. Or, conversely, one might consider a first draft a framework of individualized, itemized plot-points, merged together to form a slightly more coherent overall concept. (Refer to Outlining if necessary.) Some writers’ outlines organically morph into first drafts, while others more resemble Outline v2.0. Some writers will hone and rewrite their outlines as a completely separate entity, until they feel comfortable beginning a first draft that might seem like a nearly finished novel. Doesn’t really matter what your outline looks like—so long as it’s comprehensive enough to fulfill your needs as an effective blueprint for your subsequent fictional work.

Typically (again, not always, but often) one’s outline will be plot-centric. Meaning that a writer is attempting to cobble together a cohesive plot from A-to-Z, but little else at this point. Some writers won’t attempt to define or hone their characters’ personalities and motivations, or locations/realms until starting to draft their story. Only during a first draft will a writer begin to overlay bits of literary muscle and flesh to plump up their outline’s skeletal framework.

Q. Should I outline before beginning a first draft?

A. It’s not mandatory. While both practices can be extremely important to story development, creating an outline isn’t absolutely necessary before beginning to write a first draft. S’up to you!

Q. Must my outline continue chronological from the first page of a story until the last page?

A. No. Some ideas begin mid-story, and an outline can continue forwards or backwards. Other writers will pause to create a partial outline only if they’re bogged down in a scene or chapter. Again, an outline is simply a tool that can help a writer move forward and/or more fully develop incomplete thoughts. If that tool isn’t necessary, there’s no need to utilize it.

Q. What’s the difference between a first draft and a second draft?

A. Depends upon your approach. There’s really no structural guideline between a first and second (or third, or fourth, or fifth…) draft. Typically, any subsequent draft is a continuation of those alterations and additions begun in a previous draft—although in reality, one can transform a first draft into a final polished manuscript, if that’s the way your brain works.

For many writers (myself included), a second draft is really a mishmash of multiple, partial re-edits and rewrites. Personally, I’ll outline any scene or chapter as it occurs to me, sequentially or not. Even if I’m just beginning a novel, should some obscure Act III scene come to mind, I’ll outline that immediately, while my thoughts are still fresh. And should my story’s conclusion gel in my head—very often I begin a story with only a hazy ending in mind—I’ll immediately stop writing and draft as much of my last chapter as I can. Once I know, or even intuit, my conclusion, I find it much easier to move my characters toward that final destination. Far fewer wrong turns or dead ends, once everyone in my story knows where they’re going, and why.

Q. How complete should/must my outline be?

A. Again, totally your call. An outline (or first draft) can be as simple or complex as necessary for your needs. For some, a few random Post-It Notes. For others, an Excel spreadsheet. But once you’re certain of your way forward, those tools have served their purpose. I create an outline for multiple reasons. I’ll include a detailed timeline, should I find myself writing various characters who need to connect in a later scene or chapter. When necessary, I’ll time-stamp hours and/or days (e.g.; TUESDAY 4:30PM) to keep myself aware of the clock ticking. Too often, when writing side-stories or back-stories, it’s very easy to muddle times and dates. One thing about a book’s ending—everybody best show up on time.

I’ll also use my outline as a ‘call sheet’—reminding myself which characters are in any particular scene, when they appear and why—just so I don’t inadvertently sideline someone, or overload a scene with needless characters. However, it’s imperative, when writing a new scene, that every character is ‘accounted for’ right up front. Each character should be ID’ed within a paragraph or two—an essential part of scene-setting—to avoid sudden ‘unexpected appearances’ later in the scene… even if those character do little but sit silently in a dark corner and scowl. They must be presented to readers ASAP.)

My outlines typically begin small—maybe a page or two of hastily jotted ideas, sometimes on Post-It Notes that pepper my bulletin board. As my story progresses, I find myself adding bits and pieces of data and plumping out a scene’s core elements in various ways— even including snippets of dialogue or scene-setting that I might otherwise forget if not notated in the here-and-now. By the time I finish my novel’s final draft (usually 350-400 pages) my outline will have expanded by 40-50 pages. So, yes, an outline can be a multi-faceted tool for those of us who need constant reminders of where, when, where, why and how I’m attempting to tell my story.

.

• Next post • Previous post • Index

.