A notebook for fiction writers and aspiring novelists. One editor’s perspective.

Next post • Previous post • Index

The Pillars of Success:

. . . .The Fundamentals of

. . . . . . . .a Successful Novel

Also: The Hierarchy of Competence

An athlete must be fast and agile. A scientist curious and logical. A watch-maker nimble fingered and methodical. A comedian funny. So what exactly are those attributes that a writer must possess to become a published author? Is there a single, foolproof, absolute secret to a newbie writer’s impending success? If so, nobody’s told me. However, a few fundamental qualities, either designed by nature (an innate instinct) or nurture (the process of learning) are probably well worth knowing before you embark upon your journey.

These quasi-laws of Literary Physics—the so-called pillars of success—can serve as cues as to who may be more likely to publish a novel. If lacking one or more of these qualities, are you doomed to never finish or sell a novel? Should you stop writing? Not if you love doing so. Best-sellers have been occasionally written by steadfast, tenacious, pillar-lite souls, despite the odds. And, by all means, give it your best shot. You have my blessing to prove the odds-makers wrong.

Those Pesky Pillars.

Ah, but I digress. Pillars. Depending upon who you ask, three or four such pillars exist. A fifth may provide the proverbial ace up your sleeve and the sixth is a bona fide soul crusher. The problem is, not everyone agrees as to what these pillars actually might be. If you Google the pillars of successful writing, you’ll get an eyeful. I’ve found (in a snappy 0.0874 seconds) the following assumptions:

Ethos, Pathos, Logos. Aristotle, the old Greek dude, coined the original foundations of persuasive communication. Ethos, meaning credibility and acceptance (the readers) of your fictional reality. Pathos, meaning emotion. Drama. Tension. Make it larger than life (if only subliminally), and keep it coming. Logos, meaning logic. Logical characters. Logical story arcs. Because illogical writing makes for weak, unimpressive and occasionally stupid novels.

Variations on this theme are: Aspiration. Inspiration. Perspiration. (Clever! And, yes, all necessary elements.)

Theory, Practice and Consumption. (Theory meaning learning the craft. Practice meaning practice. Constantly. Consumption meaning knowledge. Read novels. Read non-fiction. Read how-to primers. Immerse yourself in all things literary.)

Know your audience. (What’s your genre?) Have a purpose. (What’s your message?) Adjust your style. (Find your writer’s voice.) Repeat the Process. (Practice. Write often. Don’t give up!)

Concept. (A writer’s idea, premise and plot.) Conflict. (Drama. Always.) Characters. (A fully developed protagonist, fully developed antagonist, fully developed extras.) Theme. (The reason you’re telling the story. There’s always a reason, even if we ourselves are unaware when we begin.)

Curiosity. Creativity. Productivity. (All self-evident.)

Plot. Character. Setting. (Ah, this one sounds familiar…although more likely story-based components, rather than a success-based adage, imho. But no less important.)

Emotion. Logic. Credibility.

Mindset. Environment. Tools.

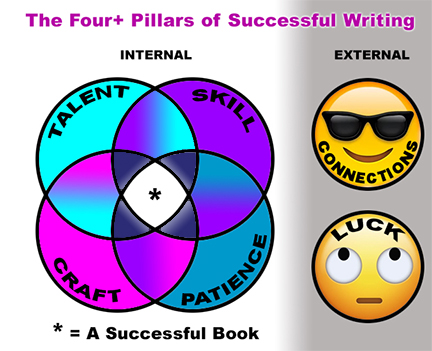

…and the list goes on. Our pillar-theories may vary (we theoretical pillarists), but our intentions are both admirable and identical: The ultimate success of the writer. So, with that in mind, I’ve included my own blend of literary pillarizing. Although I am suggesting a slight twist. I’ve even drawn a Venn Diagram to explain (…a picture being worth a thousand words, after all).

.

So let’s dissect this pillary thing, shall we?

The Internal Factors.

• Talent (An innate, inborn capability to concoct and produce a well-written novel). Talent is that inherent ability to tell an interesting story in a unique voice. And then to impress agents and/or publishers with a sterling query. Like chess masters, divas, athletes and multi-platinum selling singer/songwriters, you’re either born with a certain talent or you’re not. Me, for instance. I love music. Learned to play guitar—badly. Practiced daily for years, but never broke out of that meh! stage. The mathematics of music confounded me. (Change keys from G to B-flat? Whaaaa?) I also have a singing voice like a frog in a hailstorm. So no, no amount of dedication was ever going to help. We all can’t be everything we want to be. Just sayin’. Then again, everything we might become is certainly worth a shot. • This attribute is inborn; out of your control or your ability to learn.

• Craft (Technique. Absorbing information. Trial-and-error. Attempting to establish an authorial voice.). Craftsmanship is your ability to learn and develop the rules and mechanics of writing. It means perusing ‘how to’ books on grammar, plotting, narration and dramatic pacing. It means perhaps taking classes or joining a writer’s workshop (which I highly recommend). Or finding employment in a writing-based job—copy writing, advertising, journalism. Or reading manuscripts. Teaching English or Literature. Me? I was a newspaper film critic for several years with a strict 750-word ceiling. Man, that job taught me more about self-editing, about whittling down excess verbiage and getting to the point, and greatly honed my writing abilities. Sometimes it means starting a novel or two, if only to fully develop the necessary knowledge to write a novel that sells. Write until you find your own unique, authentic authorial voice, and then write some more. Realize that it’s okay, perhaps even essential, to blunder, to learn from your mistakes, and then keep writing. • This attribute can be taught and learned.

• Skill (Competence, Expertise, Finesse, Finding your voice). Skill is your ability to realize your potential (an infusion of self-confidence), and then utilize that expertise to its fullest extent. Skill is what results from learning your craft up, down, and sideways, inside and out. Skill is basically Craft 2.0! • This attribute can be taught and learned, but ultimately it’s a personal choice to educate yourself until you’re all but assured of eventual success.

• Patience (Determination, Perseverance, Practice). There’s no other way to finish a novel than to begin. By writing a single line, an infectious opening paragraph, a fully developed first page, you’re making a psychological pact with yourself—that you and your brain are in this for the long run. You’re here for the whole enchilada. Writing a novel is like raising a kid: Less sleep, fewer weekends down at the disco, lots of self-doubt and even a little self-pity. (A little is okay. You’re a struggling artisan after all.) You may be constantly apologizing to friends and family for your prolonged absence. You’re committing yourself because you know you’re competent and talented, even though nobody (yet) may recognize those talents. You’re aware that thousands of other novice writers exist with similar dreams—and if they have a shot, so do you. So you take the leap. Write a page, then another, then another…because that’s the only way home. • This sort of inner drive can’t be taught or learned—and may take years of practice and dedication.

* The Sweet Spot. (That tiny white diamond in the middle of the diagram.) If one has the talent, craft, skill and patience to finish a manuscript and begin to pitch the book, the chances of finding an agent or publisher are typically far better than those writers who find themselves lacking in one or more arenas. (If you do find yourself lacking, doesn’t mean that you can’t learn and grow and, in time, prosper.) Which only leaves a single potential speedbump standing between you and Stephen Kingdom—and that’s luck. But read on….

The External Factors.

• Connections (It’s who you know and who knows you). This one may feel a bit disingenuous—but the simple fact is, nepotism and associatism exist and, by all means, if you got it, use it. Is your uncle an editor at Macmillan? That one’s a slam dunk! If you know somebody who knows somebody who works at Simon & Schuster (even in the mail room), or if your great aunt used to date a literary agent in Tuscon—yes! Follow the bread trail. You never know.

P.S.: If you have no connections, and you’re one of those charming extroverts, capable of perfecting your own bow tie, of making a marvelous (shaken, not stirred) Martini, who’s proficient at making friends and connections wherever you go (and if so, good for you) then go for it! As they say in Hollywood, schmooze ’til you lose!

• Luck (Rolling the cosmic dice). This one’s the looming nightmare, the nasty, giggling gremlin who pervades every writer’s hopes and dreams of a book sale. Luck is fickle, unorthodox and totally unpredictable. If your exquisitely written manuscript lands on an agent’s desk who’s hungover or is having marital problems, you may be inexplicably overlooked. A publisher’s assistant who’s going on vacation tomorrow? Same results. Your e-mail query ends up in a junk mail folder. Maybe your insanely well-written novel reminds an assistant editor of a less adept novel that crossed her desk last month, which was nevertheless accepted and that fortunate writer has just signed a contract for a juicy royalty and certain fame. Or maybe you’ve somehow overlooked a typo on page one. (I’ve done that!) It’s sufficient to turn potential good luck to unfortunate, rotten luck.

Speaking of rotten luck, I’ve known a few fiction writers who’ve lost manuscripts in hard-drive crashes, and (of course) the backup’s been corrupted and…well, shit does happen. Aware of Coronal Mass Ejections? Y’know, those giant plasmatic, magnetic fields occasionally spit from the Sun? A lightweight solar flare will cause a pretty aurora. A direct hit from a heavyweight magnetic distortion can potentially fry power grids. Electronic files can (theoretically, at least) be damaged or erased by such an incident. So here’s a new rule. Maybe one of the most important. Rule #98: Make a hard copy (paper) back-up of your manuscript every now and then, even if you’re still working in draft mode. See Finagle’s (aka Murphy’s) Law. But brace yourself.

Here’s a fitting, random comment about blind, stupid luck. Years ago, producers greenlit a film about John Lennon’s life (John and Yoko: A Love Story). The gifted actor chosen to portray Lennon was named Mark Lindsay Chapman. Lennon’s killer was named Mark David Chapman. Yoko Ono so freaked out at the eerily unlikely coincidence that another actor was ultimately recruited to replace him. True story. Bad luck. It exists.

The Hierarchy of Competence

Whether writing a novel or attempting to learn (and master) any of life’s million or so teachable lessons, there’s a savvy little social model that may explain the ‘Pillar Approach’ in somewhat different terms. American Filmmaker Noel Burch’s The Hierarchy of Competence dictates:

.

- Unconscious Incompetence: Meaning that I’m unaware of a particular skill, or of any necessity to even utilize that skill. (Johnny doesn’t know the difference between a noun and a verb, nor does he care. But, hey, he’s just read a good book and the author’s raking in some pretty big bucks. Johnny rationalizes that anyone can write a novel and make a fortune. It’s not that difficult, right?)

. - Conscious Incompetence: I’m becoming aware of a need for a particular skill, and the rationale for learning the appropriate lessons, but nahhh, I can probably get along by faking it. (After scribbling out 5 atrocious pages, Johnny’s confused and angry to realize that he knows very little about writing a novel. And yet, he persists.) By the way, the persistent part? That’s every writer’s make or break moment—the decision to practice and learn and, hopefully, to go the distance, is crucial.

. - Conscious Competence: I’ve learned a thing or two about a particular craft and, hey, maybe I’m not half bad. But I’m aware there’s lots more info to absorb. (Johnny understands the basics of plotting and the fundamentals of fiction writing by now. He’s read Strunk & White. He’s read Bird By Bird. He deconstructs novels that he’s read and likes—trying to figure out what ‘makes them tick.’ He’s even signed up for a creative writing class. Sure, he believes he’s pretty good at writing, but he knows he could be better. Time to read a few more ‘how to’ books and then it’s back to the keyboard. Or sharpen that pencil.)

. - Unconscious Competence: After a few years—yup, years—of practice, of trial-and-error, of finishing a dozen short stories that receive good feedback, I’m becoming a skilled writer, in total control (and harmony) with my talent and craft. (Johnny sits down in front of a computer and new worlds unfold before his eyes. He realizes that the act of writing—drafting, composing, editing—is no longer drudgery and anguish, but has recently become a labor of love. Sure, occasional moments of self-doubt, of lethargy and uncertainty may linger, and yet with utmost confidence, Johnny begins his novel. He’s certain he will finish. His thoughts afire, his fingers dance over the keyboard, working in nearly effortless tandem. (Because, yes, those moments do exist.)

Bottom line: Don’t let anyone—not me, certainly not this post—dissuade you from trying. From persisting. Write your freakin’ ass off, until you succeed or something better comes along. So if I can leave you with anything, it’s this:

“To infinity…and beyond!”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . — Buzz Lightyear

.

Next post • Previous post • Index

.