A notebook for fiction writers and aspiring novelists. One editor’s perspective.

• Next post • Previous post • Index

Getting Down To It.

So maybe you’ve tried writing a few short stories. Or you’ve started a novel, cranked out a few pages or maybe a few chapters, but you’ve found the process… difficult. A bit daunting. Overwhelming. So let’s boil the process down to the bare bones — and perhaps get a better feel of what starting a novel is all about. So, for the moment, let’s forget about developing any sort of writing style, about pushing through writer’s block and other down-the-road potential obstacles, about winning that Pulitzer or interviewing with Oprah. For the moment we’ll stick to the preliminaries.

I’ve mentioned this before, but it’s worth repeating: There’s no single, best, one-size-fits-all approach to beginning a novel. Some first-time novelists simply plop themselves down in front of a notepad, a typewriter (because those still exist!) or a PC and begin to peck out a first line, and then another. And another. You’re starting out cold turkey, ready to bang out 300 or 400 pages without a second thought. You’ve got a story to tell and, by God, you’re going to tell it. Because if that’s your style, your intent, go for it! Writers have been writing first novels by the seat of their pants (some of those efforts destined to become best-sellers) for hundreds of years. You can’t argue with tradition.

Or maybe you’re a perfectionist. You’ve been planning your novel for months or even years — getting yourself mentally prepared, but not quite ready to, y’know, do the deed. You’ve read every How-To writing book ever printed, and you’ve memorized Strunk & White. Maybe you’re on your way to a Ph.D in creative writing. (Is there such a thing?) You’ve crossed your proverbial I’s and dotted your perennial T’s and only now, locked and loaded, are you ready to dare tap out those first few sentences.

Either way, realize that this brazen new millennium offers new and exciting (or new and terrifying, depending upon your POV) approaches to prepping, drafting, writing and selling a novel. The Internet has changed the way we gather and research information, interact with other writers to learn a few trade secrets or swap stories, tips and secrets — Reddit’s r/writing sub for example, or NaNoWriMo, Writer’s Digest, Writers Helping Writers, Inkitt or Wattpad — and how we find agents, editors and publishers. (Publisher’s Marketplace, for example.) New emerging (or recently emerged) markets such: Audio, ebooks, flash-fiction and fan-fiction Websites and how-to apps proliferate. Total strangers will tell you what to do, how to do it, and will occasionally rip you and your work to pieces with the joyous dexterity of a seasoned serial killer. Emotionally drained, you’re left to wonder, Am I really a horrible writer? Or is that new best friend and critic of yours just some rando psychopath? Sometimes it can be hard to tell. But refer again — and as often as necessary — to Rule #3. Write to please yourself. I call it my self-inflicted sanity rule.

Not to mention that you’ll come across people like me; well-meaning souls who harken our presence and thrash about with an austere sincerity (or else an utterly false pretense) eager to share our fabulous secrets of fame and fortune like so many boardwalk carnival barkers. (Another rule of thumb: If somebody’s asking you to pay for their unsolicited time and advice, think twice, fact-check their credentials and, if you smell dead fish, don’t be afraid to run screaming into the night.)

Because, basically, writing a novel can be a lonely, isolating endeavor, and trusting oneself is paramount. Your guess about what makes a best-seller is as good an assumption as anybody else’s best guess. So, yeah, relying on your own intuition and common sense is a safe bet. If you get stuck or lost along the way, sure — it’s okay to seek advice or second opinions. But always remember that you’re captain of your own ship. If you find yourself sinking, it’s okay to swim for shore. But if you can weather the storms and make it to port, there’s no sweeter feeling. The first time you see your very own ISBN and/or Library of Congress PCN — few other thrills can compare. Because publishing a book feels very much like landing on the moon or skiing the Matterhorn. For anyone staring morosely at a blank screen, contemplating tapping out those first few pages, just be aware that the long journey ahead can be well worth the effort.

And if you don’t try, you’ll never know for sure.

So perhaps it’s time to explore that Yellow Brick Road. So let’s cut to the chase, bury that witch and skip forward. (Cue the Munchkins!) Because whether you’re contemplating beginning a novel or you’ve already started (or started over), I’ve listed (below) what I consider to be variations of that essential first step.

But give yourself permission to engage in a bit of introspection. A little self-analysis. Ask yourself a few basic Why? questions. Don’t worry, it’s painless. Ain’t nobody’s keeping score. And there are no wrong answers. But understanding your core motivation for writing is, I suspect, more important than you may realize. For instance:

- Why have I chosen to write this particular narrative?

An easy question. Because any consideration short of I really don’t have a clue is acceptable. Writing for the sheer joy of writing is a completely okay. Writing to make a moral or social or philosophical difference is fine. Even writing to quiet that incessant static buzz between your ears is acceptable. What’s static after all but a frequency looking for a receptor? Writing may be that receptor. Many writers find that writing fiction quiets the brain, fills a void, provides meaning to an otherwise vacuous life. All valid reasons to begin writing. But if you find yourself lacking the passion of your convictions, or the tenacity to write another 300-400 pages, you’ll not get very far. A page or two. A chapter or two. Then reality sets in. Maybe you begin another story, and then another and another—your efforts never extending past that initial spurt of creativity. Sure, give yourself credit for trying, but without a game plan, without a creative goal in mind, you’ll likely find yourself unable to finish.

- What narrative voice should I use?

Options abound. Present tense? Past tense? Are your characters internally or externally motivated? Do you write from the head or from the heart? What narrative perspective works best? Writing in Third Person Perspective or First Person Perspective is a bit more complicated than simply a matter of writing I/me or he/him. Your narrative voice can greatly influence the style and tenor of your story. See Finding Your Voice (Part 3).

Because if you don’t know, readers probably won’t know either. (Also refer to What’s Your Intention.) Maybe you love reading fantasy, and you’re enamored with fire-belching dragons. However, sitting down to write about fire-belching dragons, without further consideration or contemplation, your visions will likely sputter like hot sparks on a cold day. How well do you understand your characters’ motivations? Their behaviors and personalities? What journey will they embark upon? Your story must be different, unique and—above all—calculated. Charted. Logically designed, page by page by page. Because perceiving a story is easy. Implementing those concepts—a.k.a., writing a story—requires meticulous effort, sometimes difficult, occasionally frustrating, perhaps even daunting, and definitely time-consuming. Are you ready to hang in for the duration? (See First Drafts.)

- What’s my end game? How to I best conclude my story?

Many of us have an idea, a concept, an inciting incident in mind—and little else. For some writers that’s sufficient, they’ll build as they write, but for many of us, knowing the journey and it’s conclusion is essential to our progress. When we know (or at least intuit) our end game, our characters will also know. Once we’re aware of how our story ends, it becomes much easier to choreograph our characters toward their fates, or their final destination—and with far fewer wrong turns or dead ends. Otherwise, many writers hit that ‘muddle in the middle’, and lose their way, or give up altogether. So know where you’re going, then figure out how to get there.

Excuse the worn (yet accurate) cliché: Writing a novel-length story isn’t a sprint, it’s a marathon. And even if you’re attempting to write short stories (wind sprints!) be aware of the finish line before you rush to take that first step.

- What do I risk by writing this (or any) book? Is it worth the price?

I’m no shrink, nor do I play one on TV, and I expect no Freudian answers. But are there risks writing a book? Yup. A risk of disillusionment, disapproval and disappointment, for starters. Losing touch with friends and family. Losing months or perhaps years of your life while staring at a computer screen (and wondering who’s going to pay the G&E bills). Most of us will face a buttload* of rejection, and sometimes repeatedly. Most of us who begin a novel — and brace yourself — won’t finish. Of those who do finish, a majority will not find a publisher. Of those who do, a majority will not make a sustainable living. Not trying to be a total bummer here—but those are the risks we learn to accept.

Maybe you’ve heard of the Aspiration, Inspiration, Perspiration philosophy of novel writing? If not, here’s the gist:

Aspiration is about having a desire and ambition—the eagerness — to write a particular story. Maybe it’s based on family history or a newspaper article or an old movie you once saw, and intend to improve upon. Maybe you’ve read a thousand fantasy novels and thought, I can do that! But having a specific goal in mind can be crucial to boy your joy of writing and your success.

Inspiration is simply another word for your creativity. Every chance you get, consciously or subliminally, your brain is concocting clever scenarios about this and that and some other thing. What if this happens? What if that happens? What would happen if…? Meaning, you’re comfortable concocting clever, witty characters in well-conceived settings (or realms), and then giving them something exciting, profound and memorable to accomplish or survive.

Perspiration is perhaps the most challenging of the three. Perspiration is all about your ability to persevere, page after page after page. Day after day, night after night. It’s about excusing yourself (not always, but often) when you’re friends are knocking back tequila shooters down at the Disco. It’s about potentially isolating yourself from friends and families for months or years, and about accepting criticism (when valid) and about pushing forward despite reservations and self-doubt and either the fear of failure or fear of success whispering furiously in the back of your brain. (Also see Fundamentals for a deeper dive into this philosophy.)

But enough with the negativity already! Back to the fun and frolic of telling a good story.

As previously discussed, most story ideas begin as a snippet of thought or a fragmented concept, perhaps a random daydream or a tasty soundbite thrown your way from mass- or social-media. Maybe you’ve piled on additional, if nebulous, ideas as well. Once you have a basic story in mind — either a partially considered, loosely threaded beginning, middle and ending in mind, or simply that aforementioned inciting incident — it’s up to you to expand upon those concepts into an eventual, fully-formed novel.

Do realize that no set rules exist for proceeding. If my last few posts feel unhelpful or cumbersome, no worries! (And this is as close to a disclaimer as I’ll come.) But since every writer’s brainwaves, intuitions, coping skills and experiences are unique, I’m unlikely to speak with either eloquence or efficacy to every novice writer. So take from me what you will, disregard the rest and Google your way toward any number of variable alternative sources. The great thing about the Internet; There are a million different sources and resources awaiting your arrival. (Then again, the terrible thing about the Internet is: There are a million sources and resources out there.) So choose well, Pilgrim!

As previously mentioned, one can simply sit down—with a note pad, a voice recorder (some of us do!), a typewriter or PC—and begin to lovingly craft a vision; word by word, page by page, and scene by scene. But if blindly charging forward into the fray isn’t your style, no worries! Some writers mull their stories for months or years (it’s a kind of creative procrastination) waiting until they feel the moment is ripe to actually begin a draft. However, f you consider yourself a creative procrastinator, or else suspect your impending story as being only half-baked, I offer a few suggestions that may (or may not) help you with a little forward momentum. For instance:

The Outline. I’ve already mentioned the potential value of outlining in my previous post—but it’s a valuable tool, and well worth exploring. The process may begin as little more than bullet-pointing a potential story line—although some writers use index cards tacked to cork board, or mark major plot points on a chalkboard; others will voice record their thoughts or simply jot random thoughts on a notepad or two. (I’ve tried that, but I tend to misplace notepads with alarming frequency.) If you need a refresher on the benefits of outlining, HERE it is.

The Synopsis.

While your outline allows you to essentially expand various story ideas, a synopsis is, conversely, an encapsulation of ideas. A summary. If you’re able to define your plot in a page or two or three, you’ll begin to better understand the crux of your novel. Maybe your exciting sci-fi alien encounter is really a love story. Or your tale about two army deserters in a terrible war is basically a story of finding courage. A schoolyard tale about bullies and weaklings is ultimately a story about building unlikely friendships. So a synopsis can be a quick-glance guideline or as a daily reminder of where your story’s heading. (I’ve known a writer or two who’ll tape a synopsis above their desk. Every morning, it becomes both a prompt and an an inspiration.

If creating a synopsis seems frivolous or overwhelming (and it may) take a deep breath and try this: What’s your favorite novel? See if you can write an synopsis about that book, without the pressure of summarizing your own words. Synopsize a few novels and abridging your own work may feel less daunting.

For example:

.

Amidst the rumble of an approaching Civil War, we find Scarlett O’Hara, the spoiled, teen-aged daughter of a wealthy Atlanta plantation owner, caught in her own giddy social bubble. Scarlett is clueless about the meaning of life, or the value of honor—although as the war rages, she discovers newfound courage and an inkling of character. Briefly married, she is quickly widowed by the calamity of war. Shortly thereafter, Scarlett’s beloved plantation, Tara, falls victim to the advancing Union army, and she must decide between her love of the land and her dedication to friends and family. She falls under the spell of a rebel blockade runner named Rhett Butler. The two are unsuited, but soon after the war’s end, she weds Rhett not for love but rather for his brash charisma and wealth—his ability to save Tara from the ravages of a lost war. However, their happiness quickly spirals into bitterness and remorse—and Scarlett ultimately decides that saving her home, Tara, is more important than saving her marriage. Still, she gathers the strength to hope for a brighter future.

Sure, it’s a sketchy synopsis, and incomplete (for instance, no mention of Ashley, of Melanie, or of Scarlett’s children), but it carries forth the deep core of the plot. Now, what about your story ideas? Can you define its heart and soul—even before you write word one? Discovering the essence of your unwritten novel can prove useful—and the sooner the better. Finding the essence of your story is so crucial that it’s now a rule.

Rule #11: Get acquainted with your story. Find your core elements. Because the more you know now, the fewer pages you’ll trash later.

Oh, and don’t delete your synopsis after you finish a draft or two. Agents and editors and publishers will ask for it. (At least I’ll ask.) Your synopsis can serve as your literary calling card, whence you submit your manuscript to agents or publishers.

An expanded synopsis. (Optional.) A synopsis is a synopsis is a synopsis—but like an outline or a draft, you’re constantly creating room for growth and improvement. As your plot coalesces, ain’t nothing wrong with updating your synopsis as well. Add a little padding, either before you begin to write or as you begin your first draft. It’s okay to use your synopsis (or outline) as a fluid primer or blueprint. It’s perfectly okay to update your synopsis—so feel free to add another 5 or 10 or 20 pages, exploring any newfound ideas. Make mistakes. Think fresh thoughts. Re-evaluate. Leave blanks. Every time I finish a synopsis, even a first draft, I find myself with a few dozen gaps where I’ve typed [IDEA TO COME]—and yes, again in bright, bold red—before moving along to those ideas that are freely flowing. Trust that every idea you need will arrive—and in its own damn time. Writing a novel is funny that way.

PS: If you’re one of those people loathe to leave a blank space, who must write every word precisely in chronological order, who must pen every thought with unwavering exactitude, striving for immediate perfection, my advice is this: Get over yourself! There’s no such thing as perfect writing. And certainly while attempt to piece together a synopsis or first draft! Even polished and ready for publication, there’s no single solution—no perfect sentence or perfect page or perfect chapter in a perfect book (that can’t be altered, tweaked, deleted or rethought. Every word we write (or don’t write) is a subjective impulse. Writing Harold hated his dance classes rather than Harold disliked his dance classes won’t bring your novel any closer to literary Nirvana. Do your best… and then move along. Remember, perfection is an illusion—a Siren singing sweetly on the rocks of self-importance and ultimate disillusion. We do the best we can, and we also finish the book.

By the way, it’s now a rule. Rule #100: Get over yourself!

Character Profile (Aria). Some writers choose to visualize their main characters (specifically their protagonist and antagonist) before they begin to draft out a story. They feel that creating this sort of personal bio can better hone the creative process, and can even help with plot structure. I’ve known writers who’ll look for digital images of real folks in the hopes to better establish a more familiar (and hence believable) entity in their own minds. Such intense scrutiny isn’t necessary—but it can’t hurt, either. For certain writers, depicting these people can help establish both a physical and emotional bond, even if most of these characteristics and physical attributes never make it to the page. The purpose of the literary aria is simply to help the writer’s vision.

I believe that some readers appreciate in-depth revelations of a character’s physical description, emotional band-width and various personal qualities. Others prefer to deduce such visual and emotional characteristics for themselves. So creating elaborate physical descriptions are obviously a matter of choice. For instance consider the somewhat pithy:

Marshal Dusty Yates stood at the edge of town, watching the sun rise. Yates had seen more evil in the last few days than most men would see in a lifetime. He absently brushed his fingers against the pistol holstered against his thigh and wondered if he’d live long enough to see sundown.

Or, conversely, the more detailed:

Marshal Dusty Yates, six foot, three inches of pure, mean Texan, stood grizzled and hungover at the edge of town, watching the sun rise. A hard-edged, ruggedly handsome man, Yates had seen more evil in the last few days than most men would ever see in a lifetime. He absently brushed his fingers against the smooth pearl handle of the Colt Peacemaker holstered against this thigh and, with a deep sigh, wondered if he’d live long enough to see sundown.

Both versions paint an adequate description of our hypothetical lawman, so it’s really only a factor of your writing style and the amount of detail you wish to impart.

•

When you’re ready, you’ll begin writing.

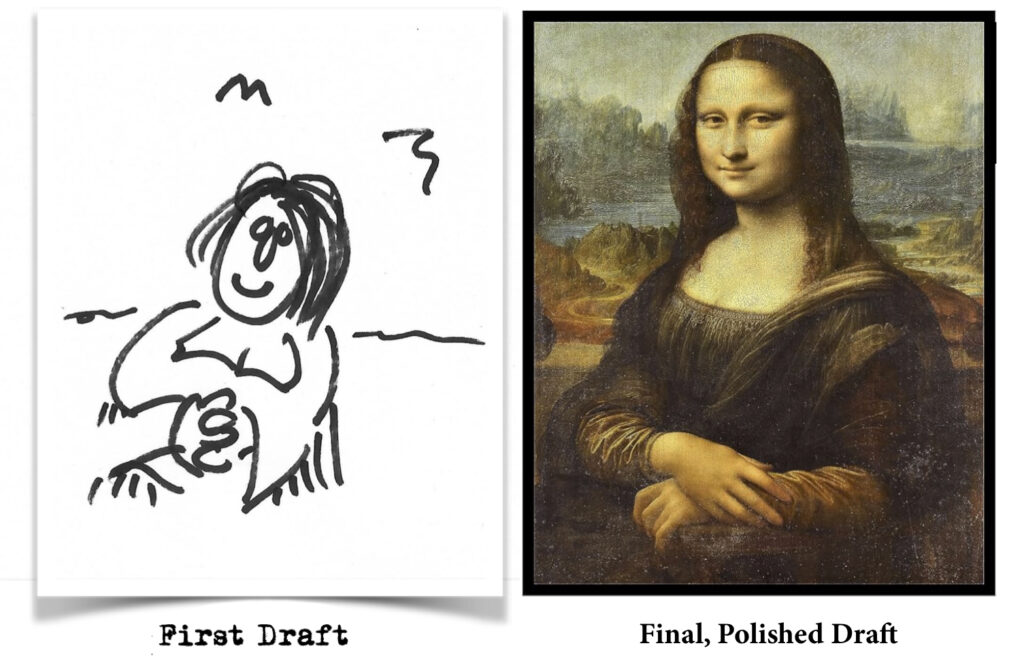

First Draft. Like an outline, your first draft is a basic tool. Yes, you’re in actual writing mode (feels good, doesn’t it?) but at this point, most writers are still slowly picking their way forward, working out the kinks, aware that much of your story may be in its embryonic stage—and subject to continual change. For most of us, our first draft will most often look like shit. Don’t sweat it! Subsequent drafts should eventually produce the book you want, and deserve.

See First Drafts for more info.

Second Draft. You’re adding additional depth and nuance to your characters and honing your plot. You’re adding colors and sounds and smells and honing both dialogue (conversations) and internal monologues (deep, inner thoughts). You’re revealing nuanced character traits and subtle innuendo, twists and turns and, if appropriate, cliff-hangers. With your first draft, you’ve already built a creature of muscle and bone, now you’re adding frizzy blonde hair and freckles and one unlaced hi-topped Keds. You’re “putting the red on the apple” as they say.

By the way, don’t think of a second draft as being a strict, chronological procedure. My use of the term ‘Second Draft’ encompasses all further drafts—third, fourth, fifth, 38th, etc. Personally, I’ll rework and edit my first 50-100 pages perhaps a dozen times, my middle second half as much and my ending—which I usually discover somewhere during the middle of my story—a few times. (Although I’ll often fuss over my final chapter quite a bit. Getting it right is essential.) But I’ll often skip jump back and forth over scenes and chapters and work on specific trouble spots—wherever my brain decides to take me at any given moment.

After I finish my first draft, I’ll typically revisit my early scenes because now I better understand my overall story, and my characters’ personalities and motivations—and I’ve gone as far as rearranging scenes or rewriting completely new opening prose to best fit the nature and nuance of my grand finalé. I never assume my opening lines will survive intact…because they rarely do.

Also be aware that while a “shitty first draft” is fairly common among writers, we all have our own systemic approaches to drafting. Because no two are alike, no two first drafts will be alike. Some writers (I believe sci-fi master Arthur C. Clarke was one) crafted one page a day — or so go the rumors — and rarely if ever revisited or redrafted a written page. If that system works for you, great! For the rest of us, however, the redrafting and editorial processes can take months. Even longer.

The Stick-it-in-a-Drawer Phase. Seriously. Put it away for a week or a month. Try to forget that you’ve ever written it. Me? I use that time to begin contemplating a new book. Or read or else OD on old movies…anything to take my mind off that work-in-progress.

Polishing. Time’s up! Read your story again with fresh brain cells. Tweak and polish each page. Cut every uncertain or unnecessary word that doesn’t want to fit, un-garble every phrase that feels plodding or slow. Fill in the gaps…even if that means adding scenes or chapters. Trim threads from the tapestry. Be sure every aspect belongs. Speed up the action or, when it doubt, truncate or eliminate the morass. If you feel something reads slow, don’t assume it isn’t. If you think it is, your readers will think so too. Definitely find ways to truncate or tweak the slow spots. Oh, and kill your darlings.

And there’s your finished novel. Piece of cake, right?

– – – – –

* Buttload = 126 gallons of wine. Seriously. A butt is a real unit of measurement. Who knew!

.

• Next post Previous post • Index

.

by

by

A blog for fiction writers and impending writers. An editor’s perspective.

A blog for fiction writers and impending writers. An editor’s perspective.